The Heavenstone Secrets

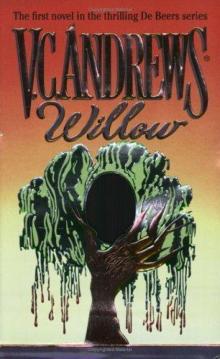

The Heavenstone Secrets Willow

Willow House of Secrets

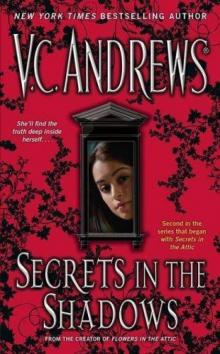

House of Secrets Secrets in the Shadows

Secrets in the Shadows Delia's Heart

Delia's Heart Falling Stars

Falling Stars Olivia

Olivia Midnight Flight

Midnight Flight Midnight Whispers

Midnight Whispers Pearl in the Mist

Pearl in the Mist Darkest Hour

Darkest Hour Secrets of the Morning

Secrets of the Morning Hidden Leaves

Hidden Leaves Brooke

Brooke Ruby

Ruby Heartsong

Heartsong Music in the Night

Music in the Night Flowers in the Attic

Flowers in the Attic Mayfair

Mayfair The Forbidden Heart

The Forbidden Heart Hidden Jewel

Hidden Jewel Butterfly

Butterfly Gathering Clouds

Gathering Clouds Gates of Paradise

Gates of Paradise Celeste

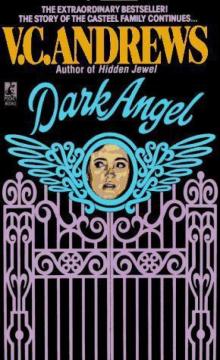

Celeste Dark Angel

Dark Angel Shattered Memories

Shattered Memories Tarnished Gold

Tarnished Gold Secret Whispers

Secret Whispers Honey

Honey Eye of the Storm

Eye of the Storm Donna

Donna Scattered Leaves

Scattered Leaves The Mirror Sisters

The Mirror Sisters Cat

Cat Child of Darkness

Child of Darkness Runaways

Runaways Dark Seed

Dark Seed Christopher's Diary: Secrets of Foxworth

Christopher's Diary: Secrets of Foxworth Black Cat

Black Cat April Shadows

April Shadows Raven

Raven Rain

Rain Petals on the Wind

Petals on the Wind All That Glitters

All That Glitters Twisted Roots

Twisted Roots Web of Dreams

Web of Dreams Rose

Rose Christopher's Diary: Echoes of Dollanganger

Christopher's Diary: Echoes of Dollanganger Into the Garden

Into the Garden Jade

Jade Secrets in the Attic

Secrets in the Attic Secret Brother

Secret Brother Whitefern

Whitefern Fallen Hearts

Fallen Hearts Heaven

Heaven Whispering Hearts

Whispering Hearts Seeds of Yesterday

Seeds of Yesterday Dawn

Dawn Cinnamon

Cinnamon Broken Wings

Broken Wings Star

Star Beneath the Attic

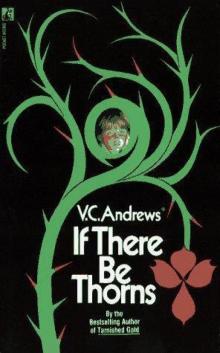

Beneath the Attic If There Be Thorns

If There Be Thorns Roxy's Story

Roxy's Story My Sweet Audrina

My Sweet Audrina The End of the Rainbow

The End of the Rainbow Delia's Crossing

Delia's Crossing Forbidden Sister

Forbidden Sister Broken Glass

Broken Glass Cloudburst

Cloudburst Daughter of Darkness

Daughter of Darkness Twilight's Child

Twilight's Child Melody

Melody Ice

Ice Out of the Rain

Out of the Rain Lightning Strikes

Lightning Strikes Girl in the Shadows

Girl in the Shadows The Silhouette Girl

The Silhouette Girl Cutler 5 - Darkest Hour

Cutler 5 - Darkest Hour Hidden Jewel l-4

Hidden Jewel l-4 Cutler 2 - Secrets of the Morning

Cutler 2 - Secrets of the Morning Wildflowers 01 Misty

Wildflowers 01 Misty Secrets of Foxworth

Secrets of Foxworth Hudson 03 Eye of the Storm

Hudson 03 Eye of the Storm Tarnished Gold l-5

Tarnished Gold l-5 Orphans 01 Butterfly

Orphans 01 Butterfly Dollenganger 02 Petals On the Wind

Dollenganger 02 Petals On the Wind Sage's Eyes

Sage's Eyes Casteel 05 Web of Dreams

Casteel 05 Web of Dreams Landry 03 All That Glitters

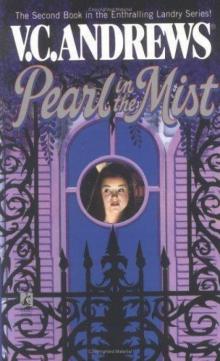

Landry 03 All That Glitters Pearl in the Mist l-2

Pearl in the Mist l-2 Casteel 01 Heaven

Casteel 01 Heaven Hudson 02 Lightning Strikes

Hudson 02 Lightning Strikes Casteel 04 Gates of Paradise

Casteel 04 Gates of Paradise The Umbrella Lady

The Umbrella Lady Dollenganger 04 Seeds of Yesterday

Dollenganger 04 Seeds of Yesterday Ruby l-1

Ruby l-1 DeBeers 02 Wicked Forest

DeBeers 02 Wicked Forest DeBeers 05 Hidden Leaves

DeBeers 05 Hidden Leaves Dark Angel (Casteel Series #2)

Dark Angel (Casteel Series #2) DeBeers 01 Willow

DeBeers 01 Willow All That Glitters l-3

All That Glitters l-3 The Unwelcomed Child

The Unwelcomed Child Shadows 02 Girl in the Shadows

Shadows 02 Girl in the Shadows Wildflowers 05 Into the Garden

Wildflowers 05 Into the Garden Early Spring 02 Scattered Leaves

Early Spring 02 Scattered Leaves Logan 02 Heartsong

Logan 02 Heartsong Shadows 01 April Shadows

Shadows 01 April Shadows Shooting Stars 02 Ice

Shooting Stars 02 Ice Secrets 02 Secrets in the Shadows

Secrets 02 Secrets in the Shadows Garden of Shadows (Dollanganger)

Garden of Shadows (Dollanganger) Little Psychic

Little Psychic Casteel 03 Fallen Hearts

Casteel 03 Fallen Hearts Shooting Stars 01 Cinnamon

Shooting Stars 01 Cinnamon Cutler 1 - Dawn

Cutler 1 - Dawn Logan 05 Olivia

Logan 05 Olivia Fallen Hearts (Casteel Series #3)

Fallen Hearts (Casteel Series #3) Dollenganger 05 Garden of Shadows

Dollenganger 05 Garden of Shadows Hudson 01 Rain

Hudson 01 Rain Gemini 03 Child of Darkness

Gemini 03 Child of Darkness Landry 01 Ruby

Landry 01 Ruby Early Spring 01 Broken Flower

Early Spring 01 Broken Flower Bittersweet Dreams

Bittersweet Dreams DeBeers 03 Twisted Roots

DeBeers 03 Twisted Roots Orphans 05 Runaways

Orphans 05 Runaways Shooting Stars 04 Honey

Shooting Stars 04 Honey Wildflowers 04 Cat

Wildflowers 04 Cat Heaven (Casteel Series #1)

Heaven (Casteel Series #1) DeBeers 06 Dark Seed

DeBeers 06 Dark Seed DeBeers 04 Into the Woods

DeBeers 04 Into the Woods Shooting Stars 03 Rose

Shooting Stars 03 Rose Orphans 03 Brooke

Orphans 03 Brooke A Novel

A Novel Secrets 01 Secrets in the Attic

Secrets 01 Secrets in the Attic Logan 04 Music in the Night

Logan 04 Music in the Night Cutler 4 - Midnight Whispers

Cutler 4 - Midnight Whispers Gemini 01 Celeste

Gemini 01 Celeste Cage of Love

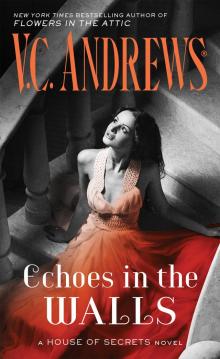

Cage of Love Echoes in the Walls

Echoes in the Walls Landry 02 Pearl in the Mist

Landry 02 Pearl in the Mist Casteel 02 Dark Angel

Casteel 02 Dark Angel Dollenganger 03 If There Be a Thorns

Dollenganger 03 If There Be a Thorns Echoes of Dollanganger

Echoes of Dollanganger Orphans 04 Raven

Orphans 04 Raven Broken Wings 02 Midnight Flight

Broken Wings 02 Midnight Flight Wildflowers 03 Jade

Wildflowers 03 Jade Landry 05 Tarnished Gold

Landry 05 Tarnished Gold Cutler 3 - Twilight's Child

Cutler 3 - Twilight's Child Capturing Angels

Capturing Angels Logan 03 Unfinished Symphony

Logan 03 Unfinished Symphony Orphans 02 Crystal

Orphans 02 Crystal Wildflowers 02 Star

Wildflowers 02 Star Gates of Paradise (Casteel Series #4)

Gates of Paradise (Casteel Series #4) Hudson 04 The End of the Rainbow

Hudson 04 The End of the Rainbow Dollenganger 01 Flowers In the Attic

Dollenganger 01 Flowers In the Attic